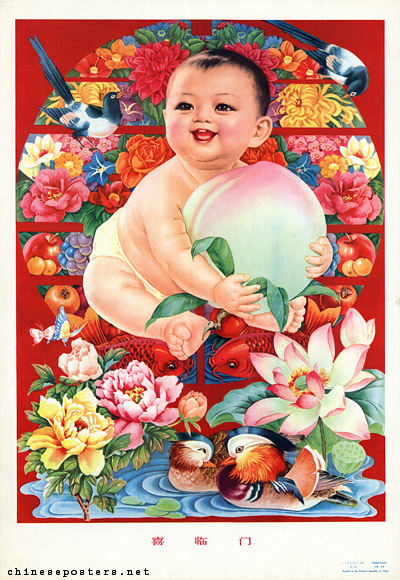

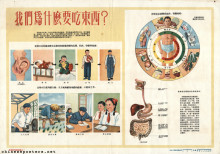

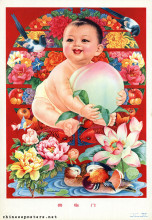

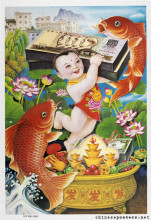

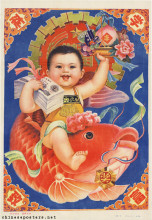

A blessing descends upon the house, early 1970s

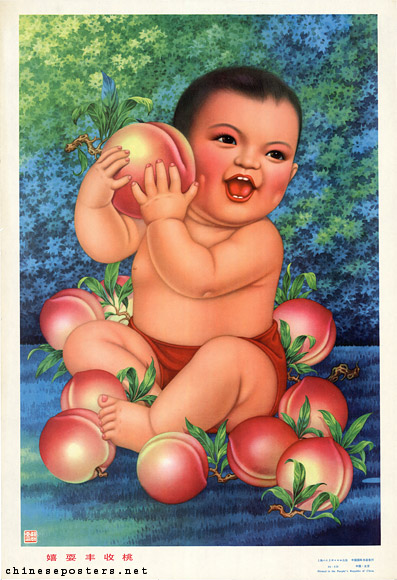

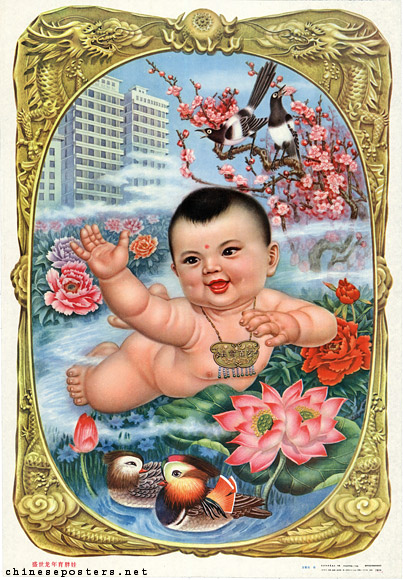

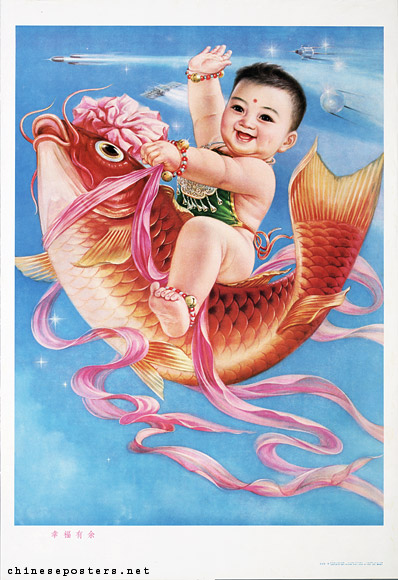

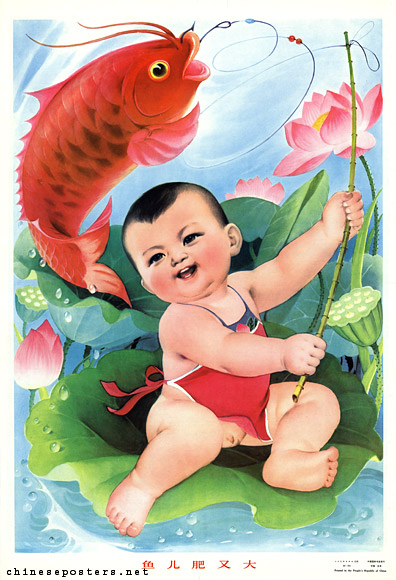

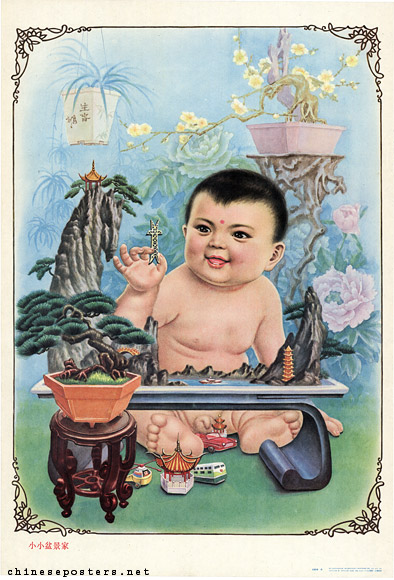

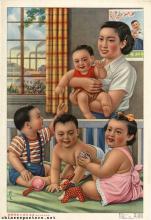

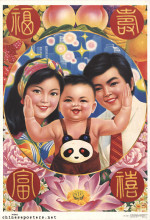

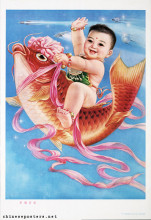

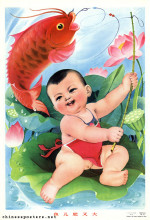

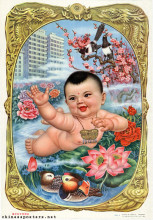

What has always been, and has remained, popular are New Year prints devoted to children. The chubby baby boys (pang wawa, 胖娃娃), particularly those holding carps, which denotes male offspring and abundance, continue to encapsulate traditional ideals of wealth, happiness, longevity, and others. Although babies are still depicted with protective charms around their necks, clutching peaches of immortality, surrounded by magpies and mandarin ducks, they increasingly are portrayed as girls.

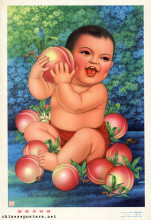

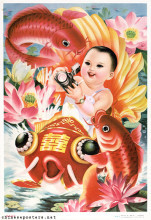

Playing with a bumper crop of peaches, early 1970s

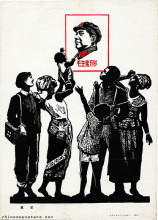

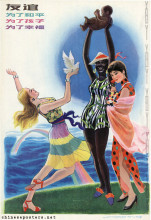

Moreover, various visual elements of economic development have started to creep into the more traditional poster-design. This started with highrise buildings in the background and soon turns to space ships and atomic symbols, crowding out traditional imagery more and more as time progressed. The visual element that these posters have in common is the dove; this bird is not presented as the traditional emblem of long life, but as the internationally accepted icon of peace.

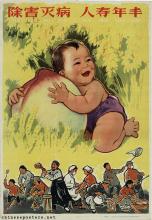

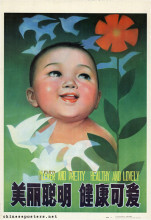

In the heyday of the year of the dragon, plump babies are born, 1987

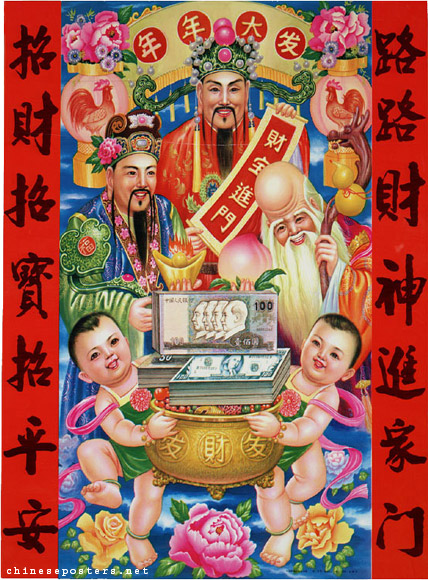

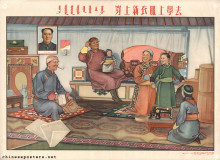

In the 1990s, non-political nianhua in the traditional style once again have been produced. The San Xing, the gods of happiness (Tian Guan, the ‘Heavenly Official’), emolument (represented by Zhou Wen Wang) and longevity (in the archetypical form of the bald-headed Shou Gong), looking young and vigorous, holding their various symbols of rank, dominate the top half of the picture. The He-He twins, symbolizing good fortune, marital harmony and wealth, hold up a copper pot adorned with the characters facai, becoming rich. The attention of the spectator is drawn to the contents of this copper pot, which is located conveniently in the centre of the print: stacks of 50 and 100 yuan RMB bills, and a sizable stack of American $100 bills.

The gods of wealth enter the home from everywhere, wealth, treasures and peace beckon, 1993

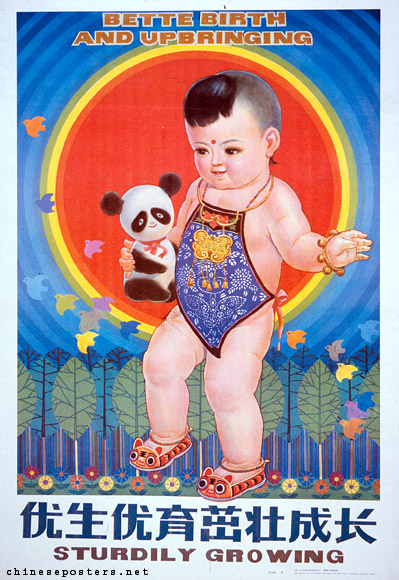

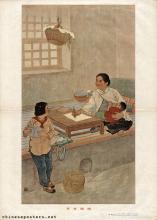

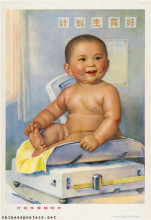

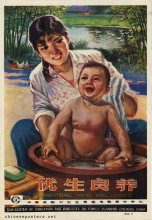

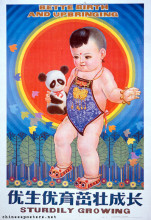

The poster ’Bette[r] birth and upbringing, sturdily growing’, produced after 1986 to support the ’one child’-campaign, uses various visual elements that correspond with traditional concepts and symbolism surrounding childbirth employed in nianhua, although it does so in a rather clumsy way. These elements include the little apron that the baby boy wears, the ‘tiger slippers,’ as well as the amulets around his neck and his left wrist. He moreover has a red spot painted on his forehead as protection against disease. However, he is not smiling. Nor is he chubby, as babies are supposed to be, and instead of holding a fish (yu 鱼, a homophone of the word yu 余 denoting abundance), he holds a rather skinny toy-panda. Other auspicious symbolism is missing as well; worst of all, the dominant colour is blue, a hue considered to be ambiguous, and the auspicious red is almost completely absent. It is hard to say how such a poster contributed to popular conformity with the message.

Bette(r) birth and upbringing, sturdily growing, 1986

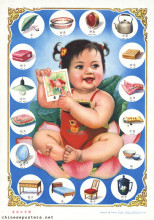

The difference between this print and an earlier one, ’The fish is fat and big’, is striking. Most remarkable is the exuberance and happiness emanating from the poster. This in itself gives the image the quality of bringing joy that nianhua ought to have. The baby, in full frontal nudity, may lack a red spot on his forehead, and he has no amulets for magical protection, but he is happy. Moreover, he has succeeded in hooking the fish of abundance in a pool of lotus flowers [lian], meaning "May you have abundance [yu] year in and year out [lian]."

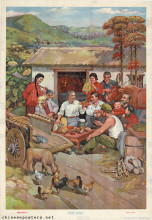

In the Reform era in particular, traditional visual elements were tolerated more than in earlier periods. In the process, the genre proved itself to be extremely adaptable to the changing circumstances. Around the 1990s, as disposable incomes rose and material wealth became affordable for increasing numbers of people, traditional baby images, but with cameras around their necks, or watches on their wrists, became the norm. But modernity creeped in in other ways too: the ‘young bonsai specialist’ above puts various elements of modernity and development in a traditional miniature landscape.