Rules and regulations for petitions, 2005

On 10 January 2005, the Regulations for Letters and Visits (信访条例, xinfang tiaoli), also referred to as complaints or petitions, first adopted in 1996, was amended by the State Council under Wen Jiabao.

The practice of writing letters or paying visits to government officials to report injustice, official misconduct or worse dates back to imperial times. According to some scholars, it is based on the Confucian ideal of commoners appealing to the better nature of officials or even the emperor. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, people could report and appeal injustices with the Imperials censors. When their complaints were not heard, or dealt with in an unsatisfactory manner, they could and would travel to higher levels of administration, all the way up to the heart of the Imperial administration in the capital.

Rules and regulations for petitions, 2005

After the collapse of the Empire and the turmoil of the decades following it, the CCP reestablished the petitioning system in the early 1950s. Aside from giving people the opportunity to air their grievances, the system was to serve other goals as well. It was set up to gather information from the people, very much in line with Mao Zedong’s theory of the Mass Line. Moreover, it was intended to allow people to participate in the deliberation and administration of public affairs, also an aspect of the Mass Line. And lastly, it enabled (public) supervision over the government and its officials.

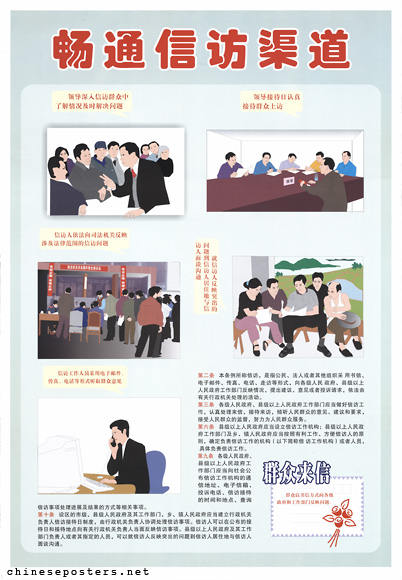

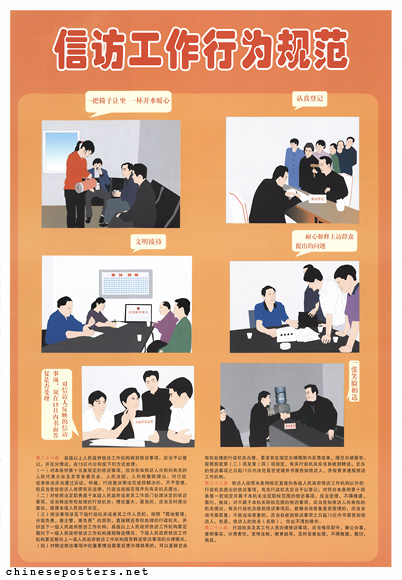

There are xinfang offices at almost all levels of government, receiving several million of petitions each year. They handle all kinds of cases, ranging from criticisms, proposals or requests for an administrative authority to violations of laws or negligence by administrative authorities and complaints against an infringement of the rights or interests of the complainant. Increasingly, the complaints have focused on appeals of judicial decisions and administrative grievances against the government.

Rules and regulations for petitions, 2005

The system seems more popular among the Chinese than going to court, a process that is seen as inefficient, expensive, inflexible and unable to solve the problem. In recent years, the plight of petitioners going to Beijing has been regularly reported on in Western media.

The posters consist of a covering sheet, stating when the Regulations were adopted and from when they are in force (1 May 2005), and provide information on Regulations 1-10 ("Clear Channels for Letters and Visits") and 21-28 ("The Scope of Letters and Visits’ Work"). This means that the set is incomplete, with Regulations 11-20 and 29 and further not present.

"'We Could Disappear At Any Time' - Retaliation and Abuses Against Chinese Petitioners", Human Rights Watch 17:11 (2005)

Xujun Gao & Jie Long, On the Petition System in China, University of St. Thomas Law Journal 12:1 (2015), 34-55

Jing Chen, "Petitioning Beijing: sub-national variation", Journal of Contemporary China 25:101 (2016), 760-776

Liu Fei, "An Analysis of Institutionalizing Petition System in China", Cross-Cultural Communication 11:2 (2015), 31-37

Qin Shao, "Bridge Under Water: The Dilemma of the Chinese Petition System", China Currents Journal 7:1 (2008)

Zhang Taisu, "The Xinfang Phenomenon: Why the Chinese Prefer Administrative Petitioning over Litigation", Student Scholarship Papers. Paper 68 (2008) (http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/student_papers/68)